A Vicar, Crucified

Simon Parke

Darton, Longman and Todd, 2013

Some books are shy. They have nondescript titles in small fonts and sit on the side-lines, patiently waiting to be picked out and asked to dance. Detective stories, on the other hand, jump out at you from your bookshelves screaming ‘Murder!’ ‘Mystery!’ ‘Death!’.

A Vicar, Crucified is one of these. The plot of the story is simple. The parish council of the windswept seaside village of Stormhaven get dissatisfied and crucify their village priest. Literally.

So far, so conventional. Brutality in detective stories is par for the course, barbarity isn’t shocking any more. Yet the murder, or even the mystery, isn’t the most intriguing part of A Vicar, Crucified.

Unusually for a book with such a dramatic title, A Vicar, Crucified is firmly a character piece. Every page oozes sarcasm, bite, and chilling observation of the world. The author, once a supermarket worker, once a comedy writer, once a vicar, knows his stuff: the descriptions of life in the church and parish community are golden. We meet the Bishop of Lewes – ‘No-one can criticise anyone with a cross from Africa!’ – giving a firm telling-off to a mouthy overweight alcoholic priest, a figure whom we’ve all met before, in an aside designed purely to showcase these characters, before we even get to the crucified vicar himself, an arrogant unlikeable man who sums up his calling as ‘why the hell not?’.

And then we come to the book’s detective, solitary contemplative Abbot Peter.

Peter is the former Abbot of a desert monastery. A thoughtful, bookish, introverted man, he cares little for possessions and his one desire in life is to be left alone. We can all sympathise. But his character doesn’t end here: like all introverted detectives, his great genius is people. He’s the son of a wandering Russian mystic (George Gurdjieff, the real-life inventor of the Enneagram; despite the moustaches, not in fact Poirot), and is an expert on the Enneagram personality system and its applications in his spare time.

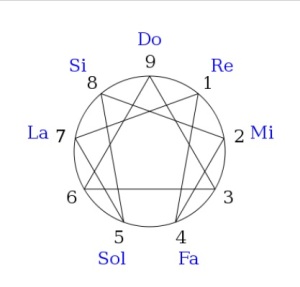

For those unfamiliar, the Enneagram suggests that there are nine personality types, each with their own specific way of failing and healthy or unhealthy ways for these traits to manifest. Type Two needs to be needed, Type Three needs to succeed, Type Five needs detachment; read up more here. And it is this, not the comparatively small manner of the crucified vicar, that makes the novel unique: the novel uses the Enneagram as a way to understand a murder mystery.

Good murder mystery books tend to be either based on logical puzzles (the dropped cigarette = suspect A, a la Holmes) or on human interaction, a la Marple and Poirot. But A Vicar, Crucified does it in an enjoyably blatant way: in Simon Parkes’s head, the murder is not about the clues but only about the people, and the murder is only a tool to see how these people interact. It’s an incredibly intriguing concept, and how the very best murder mysteries are done.

This is not to say that the novel succeeds entirely: it’s a first novel, oddly edited in places, and doesn’t quite focus enough on the murder and suspects to use the Enneagram concept as much as it could. There’s a reason why the main focus of Golden Age detectives is the murderer and victim; however interesting the detective, we have to spend less time with them than we do with the murder to follow the plot. In A Vicar, Crucified we spend a great deal of the time in Abbot Peter’s head. It’s an interesting place to be, but the novel does lose something for it, and sometimes we spend so much time exploring the character of Peter that we end up only being told, not shown, about the other suspects, and when the solution is revealed after all the time spent with the Enneagram it still feels a bit out-of-the-hat as we haven’t spent enough time with the character in question. And there is one big, great, socking flaw in the crime, which a keen reader may spot on the second reading. So…

It comes down to what you read detective stories for. If you read detective stories solely for the clues and the puzzle, perhaps avoid. But if you read them for the portrayals of life, human beings, human frailty and human satire, snap this one up now.

Your answer will likely depend on your Enneagram type.