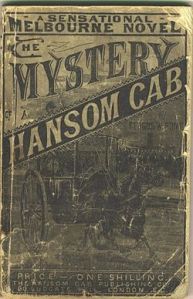

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab

Fergus Hume

Kemp and Boyce, 1886

A drunk gets into a hansom cab and leaves dead, killed by chloroform. A newcomer to town, nobody had reason to mourn him, especially his rival in love. However, his death proves to have more motives behind it than first seem possible.

The first thing that grabs you is the blurb which, like many back covers, promises a ‘mystery that will hold you, the reader, from page one right through to the end’. And, as part detective story, part murder-procedural with revelations continuing right up to the final chapter, The Mystery of a Hansom Cab certainly delivers. The pity is that the sentence before this asks ‘How could a person travelling on his own in the back of a cab been chloroformed to death?’, which promises an intriguing locked-room mystery.

A locked-room mystery that holds you, the reader, right up until…the second page, where it is revealed that somebody got into the cab with him. Just to make things that little bit clearer, he does this with the full knowledge and agreement of the cab’s driver (who later reports the murder). Twenty-eight pages later, (in a two-hundred and thirty-nine page novel!), we find out that this man did not only know the victim, but was the victim’s arch rival. John Dickson Carr, this ain’t.

The faults of the back cover aside, this is actually a very good murder-procedural, even if it does seem to shift genres throughout. For the first couple of pages, this seems a detective story: we have the (not-so) mysterious murder in the back of a moving hansom cab at the dead of night then we meet our detective, but this is done in a refreshingly novel way. For information about the crime, we cut from newspaper report to the inquest to the newspaper again, by which time Hume has neatly imparted all initial clues / alibis etc, then switch pace completely, cutting to detective Mr Gorby.

‘Hang it,’ he said, thoughtfully stropping his razor, ‘a thing with an end must have a start, and if I don’t get the start how am I to get to the end?’

In every detail in his introduction, he’s the typical Golden Age detective: initiative and eccentricity. When we initially meet him, he’s expositioning happily about the case. Since he’s a conscientious and honest policeman, however, he’s doing so to his only trusted confidante: his shaving mirror. Within three pages, he’s off discovering unusual pockets in dress waistcoats, finding landladies and, like everyone else in 19th to early 20th century detective novels, perusing the personal columns in the local newspaper.

However, the role of Main Character quickly shifts away from charming Mr Gorby to the accused, Brian Moreland and his amore, beautiful debutante Madge Frettlby. The story shifts from the crime itself to the crime’s effects, especially on Young Love: it’s rather as if Poirot had appeared at the beginning of The Mysterious Affair At Styles, then retired meekly to the background to let everyone else sort out their domestic affairs on the main stage. But the murder-procedural format has its charms and, as always in good Golden Age novels, the little vignettes of humanity seen in bit-part characters are enjoyable. Unlike other novels set in the world of millionaires and debutantes, The Mystery of a Hansom Cab is not afraid to dip its toes into the murky waters of the Melbourne underclass. The passages set among the alcoholic, syphilitic victims of this glittering world are among the best in the book, and the two worlds intertwine nicely in a way that Christie would balk at. Even if one of the characters bears the slightly improbably self-critical name of ‘Mother Guttersnipe’.

The revelations keep coming, right up until the end, though the story has the same problem that The Moving Toyshop suffered from: when the crime is sold as a ‘how?’ question, then the ‘how’ question is solved very quickly, the reader becomes less interested in the who and the why. But this isn’t a detective novel but a novel about crime, and it’s almost worth buying for the glimpses into turn-of-the-century Melbourne society. Think Law And Order set in 19th century Australia. It’s a study in crime, and the way it affects the characters associated with it. The main characters pale a bit towards the end, but it keeps you reading and, for the most part, interested. Well worth a look.

Post scriptum

‘One of the 100 best crime stories of all time’ The Sunday Times

‘Fergus Hume…went on to write a further 140 novels, but none of them achieved any real success at all.’ The back cover

The one thing, sadly, that immediately grabs you about this book is the wordlessly depressing fate of its author (and the best possible counter-argument to the idea previously expounded here). We are told (by Professor Barrie Haynes of Toronto, recounted in the introduction by H. R. F. Keating) that about twenty of these are eminently readable, which somehow makes the pathos worse. (Neither Haynes nor Keating mention which twenty). The Mystery of a Hansom Cab remains a curiosity today for this reason: the author who struck lucky once, but never again.