Agatha Christie, along with her first husband Archibald Christie, was one of the earliest British people to master the art of stand-up surfing.

Agatha Christie, along with her first husband Archibald Christie, was one of the earliest British people to master the art of stand-up surfing.

Martin Edwards, The Golden Age of Murder, HarperCollins, 2015

Agatha Christie, along with her first husband Archibald Christie, was one of the earliest British people to master the art of stand-up surfing.

Agatha Christie, along with her first husband Archibald Christie, was one of the earliest British people to master the art of stand-up surfing.

Martin Edwards, The Golden Age of Murder, HarperCollins, 2015

Obviously, spoilers ahead.

..

….

……..

…………….

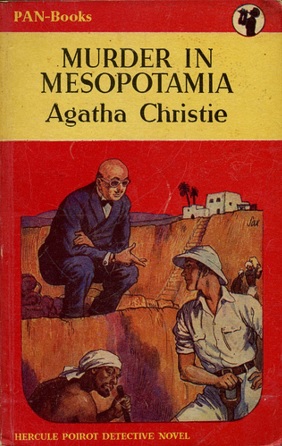

3. Murder in Mesopotamia

As a novel, Murder in Mesopotamia is interesting for a lot of reasons. For one thing, it’s one of the few Christie’s to use first-person narration: the Hasting novels have it, back when Christie was more consciously mimicking Conan Doyle. As does The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, in which the first-person narration is rather crucial to the plot.

Murder in Mesopotamia would be the same book if it were not narrated. Amy Leatheran, a gentle and practical middle-aged nurse, is no Hastings: we know that she is not staying around for more than one book, nor do we learn anything more about Poirot from her eyes. There really seems no reason for an observer to narrate, other than that it gives a slightly more personal feel to the book than the other, paint-by-numbers Poirots.

Amy Leatheran is asked to join a dig in Mesopotamia by archaeologist Dr Leidner, who is worried about his wife and wants her to be observed by a trained nurse. This is a cue for a lovely array of background details about life on a dig in Mesopotamia: something Christie was familiar with through her second marriage, to archaeologist Max Mallowan. It’s all very realistic and moderately interesting. In the background, we find out about Mrs Leidner’s first husband, a German spy. A week after Amy Leatheran arrives, Mrs Leidner is found dead. Whodunnit?

Her first husband, long thought dead. It then turns out that he was at the dig, in disguise, and Mrs Leidner didn’t recognise him. It stretches belief, but is just about plausible.

And then we find out that his alter-ego was….drumroll…Dr Leidner. Mrs Leidner’s first husband was in disguise as her second and she didn’t recognise him.

Yeah.

The Cuckoo’s Calling is about the death of a model, Lula Landry. A good part of the subplot concerns her life in the public eye, which the photo manages to convey brilliantly: the cameras surrounding her, above her head; the set of her shoulders; the vulnerability in depicting her in nightwear.

A slightly smaller part of the subplot concerns her attempt to find her own identity: as a young woman growing up, working in an isolated profession; as an adopted child; as someone of mixed race heritage trying to get in touch with black culture, struggling against the family who had tried to wash her identity white.

Yes…about that last one…

“As to the man’s psychology, that’s obvious enough. He’s mad, of course”

Anthony Berkeley, The Silk Stocking Murders

Spoilers! Please do not read on if you haven’t read Career of Evil.

…

… …

… … …

… … … …

… … … … …

Throughout the three Cormoran Strike books, we’ve been learning steadily more about Robin Ellacott, his golden-haired secretary. In A Cuckoo’s Calling, she is a fairly bland character. A nice girl, with a nice house, nice family, and a boring fiancée. Working as a temp, she wanders into Strike’s office and stays.

In The Silkworm, Robin grows as a character a little bit more. We see layers that we didn’t know were there, and that she had forgotten about completely. She turns out to be a naturally good investigator, an adept driver, amateur psychologist…slowly, Strike comes to give more of his work over to Robin, until she steadily becomes his partner. We find out that Robin was studying at university, with dreams of working for the police, before mysteriously dropping out. The tensions between her and her accountant fiancée, Matthew, become greater as Robin grows away from him and spends more and more time at the office.

Matthew’s theory is that Robin is in love with Strike. The hours spent at work, the new light in her eyes…We, the reader, don’t see an affair. We see that Robin is simply in love with her job. And, by Career of Evil, she is taking on cases as well as, if not better than, her boss.

Ah, yes. Career of Evil.

Midway through the book, there is a ‘revelation’: a ‘revelation’ that seeks to explain Robin’s claustrophobic relationship with Matthew, why she left university, why such an intelligent, driven woman is working as a temp…

We find out that she was raped as a teenager.

This leaves an extremely unpleasant taste in the mouth.

Almost certainly Rowling’s intention. Career of Evil is intentionally a darker book than its predecessors. We go beyond cartoonish violence into seeing the impact of crime on real life: fair enough that it should involve our main characters.

But with that said, sexual violence has become a cliche in detective fiction: a cheap, easy, gratuitous way to make a story dark or adult. As we are repeatedly told by Strike’s internal narration, it makes Robin into someone whose life has been defined by those twenty minutes.

What Rowling is doing is admirable, but some of the implications are a bit unsavoury.

But, leaving all of this aside, there is an alternative explanation.

We are far from the sunlit, uncomplicated days of Poirot and Marple. To be a detective nowadays, you need some kind of backstory, some kind of motivating trauma. It’s probably quicker to name those who don’t have this, but to give a flavour:

Adam Dagliesh, Tony Hill, Thomas Lynley, Quirke, John Rebus, Lisbeth Salander, Scott and Bailey, Vera Stanhope, Kurt Wallander….Strike himself has his father, his mother, his leg and Charlotte.

When we met Robin originally, she was an archetype: the nice girl with the nice job and boring fiancée, who discovers another, more exciting life and runs headlong into it. The nearest parallel in popular culture is probably a Dr Who companion: it’s a typical ‘gate to another world’ story, except that the world Robin discovers exists (sort of) in real life. The cliche of past trauma actually gives Robin more independence, because it takes her away from the archetype and back to one character, with one story, making one specific set of decisions.

Which mirrors, quite nicely, Robin’s transition from secretary to detective. In the first book, we know nothing about her character; she mainly makes the tea. In the second, as she goes out investigating we learn more about her life with Matthew. It is in the third, when she finally gets a full backstory, that we see her following up her own leads and detecting in her own right.

The increasing emphasis on Robin’s character, her family woes and her multi-layered backstory come as Robin grows from secretary to detective. The fashion is for our investigators to come with a traumatic past and family trouble. Robin-as-secretary had none of these things, Robin-as-detective does.

It’s a subtle point: perhaps a kinder interpretation than that Rowling is dwelling on something that perhaps should have been mentioned and then let alone. But ours not to judge.

Career of Evil

Robert Galbraith

Sphere, 2015

Things are going well for Cormoran Strike, private investigator. And then someone posts a severed leg to his office. Robin, his beguiling and innocent secretary, asks hypothetically how many people could possibly want to do such a thing. We’re off to a flying start when Strike simply replies “four”.

Career of Evil takes a very different tone to the previous novels. There was nothing dark about The Cuckoo’s Calling – the deaths were clean in Christie-fashion. In The Silkworm, the gore took on a gothic, macabre quality and we never quite believed in it.

In Career of Evil, we have…domestic violence, multiple instances of child abuse, multiple instances of rape, dismemberment and a sequence where a prostitute gets stabbed in the stomach before her fingers are cut off. It’s less a detective story and more a police procedural, as we travel round with Strike and Robin as they investigate the four suspects: thug Terenence Malley, Strike’s abusive ex-stepfather Whittaker, domestic abuser and psycopath Donald Laing, and domestic abuser and pedophile Noel Brockbank. It’s a merry crowd.

To give light relief, we briefly meet two people with BIID, or Body Integrity Indentity Disorder – the desire to amputate a specific (healthy) body part.* Their meeting takes place in an art gallery cafe. It’s an intentionally humorous scene that gives us observations like this:

Robin suddenly found that she could not look at Strike and pretended to be contemplating a curious painting of a hand holding a shoe. At least, she thought it was a hand holding a shoe. It might equally have been a brown plant pot with a pink cactus growing out of it.

It’s a repeated, and rather boring, criticism of Rowling that her success is thanks to plot not writing. Reading the Cormoran Strike books tells a different story: that maybe the Harry Potter books are written simplistically because this fits their fairytale quality, not because this is Rowling’s only style. In Career of Evil, we don’t so much read about but feel the small Scottish town of Melrose or a military base on Cyprus.

And for all the gore, Rowling is a master of understatement. Early on in the book, we meet the parents of a suspect’s former wife: a woman he terrorised, abused, and made infertile by ‘sticking a knife up her’. All the pent-up pain that this lack causes, the children and grandchildren stolen away, is made viscerally real by her mother’s way of making the best of things:

“But she and Ben have lovely holidays,’ she whispered frantically, dabbing repeatedly at her hollow cheeks, lifting her glasses to reach her eyes. “And they breed – they breed German – German shepherds”.

As the books progress, so Rowling peels back her characters layer by layer. Strike’s ex-fiancee Charlotte is barely mentioned: he has moved on, and so have we. We do see more of his mother Leda, and what was originally a few lines about the ‘supergroupie’ becomes a picture of a complex character: a woman who will take an abusive psycopath into her squalid home without a thought for her children, but also a woman for whom it would have been impossible “to walk past a boy of her son’s age while he lay bleeding in the gutter…the fact that the boy was clutching a bloody knife…made no difference at all”. Here we meet Shanker, Strike’s nefarious contact with the underworld and Leda’s adopted son.

We see a lot more of Strike’s military past too. It’s impossible to stress how deeply refreshing Rowling’s take on the Army is. It’s an organisation that contains heroes like Strike and psycopaths like Laing and Brockbank, and no comment is made on this. For *once* an author shows us both sides instead of total glorification or condemnation.

What we learn about Robin is fairly divisive. It adds a small amount of depth to the character, but takes away quite a lot of her status as Everywoman; this may have been Rowling’s intention. And it may be no coincidence that the increasing emphasis on Robin’s character, her family woes and her multi-layered backstory comes as Robin grows from secretary to detective. The fashion is for our investigators to come with a traumatic past and family trouble. Robin-as-secretary had none of these things, Robin-as-detective does. It’s a very subtle point, and a kinder interpretation than that Rowling is dwelling on something that perhaps should have been mentioned and then let alone – but ours not to judge.

There are some bad points. It’s not clear why Strike was certain it was someone he knew who had sent him the leg – surely he’s made a lot of unknown enemies in his time. The segments throughout the book written from the killer’s perspective are a bit overdone and detract from the tension rather than add to it. The scene-setting that worked so well in The Cuckoos Calling seems to flag a bit here – all the geographic elements are there, but the culture of London takes a bit of a back seat apart from a couple of mentions about house prices.

But these are very, very minor quibbles. Against this, we see moments like when Rowling’s evocation, humour and dramatic tension all come together in one glorious sentence as Shanker shields an abused girl with one hand and raises his knife with the other. We read about his “gold tooth glinting in the sun falling slowly beind the houses opposite”.

Worth twenty quid to read that alone.

***

*BIID.org.uk contains the following sentence in the introductory section on their website: “Therefore, to become a better person, they feel that a certain limb or appendage will have to be amputated. Unfortunately, there are no known surgeons that will carry out this type of amputation without a medical reason to perform the operation[!]” It’s almost impossible to judge whether this is a real disorder and a very subtle parody.

When you come across the quote from an “eminent neuroscientist” named Dick Swaab, you may assume the latter. Uncertainty returns on the discovery that he’s a real person.